August 05, 2016

Avoid Being Blindsided by Rush Orders

Heightened demand for quick turnaround requires flexibility and a culture that embraces speed.

With the breakneck pace of 21st century business, distributors have been forced to ramp up their operations to satisfy customers’ instant needs. Whether answering questions via social media or hosting e-commerce stores for 24/7 access, business owners must be informed, available and attentive virtually at all times.

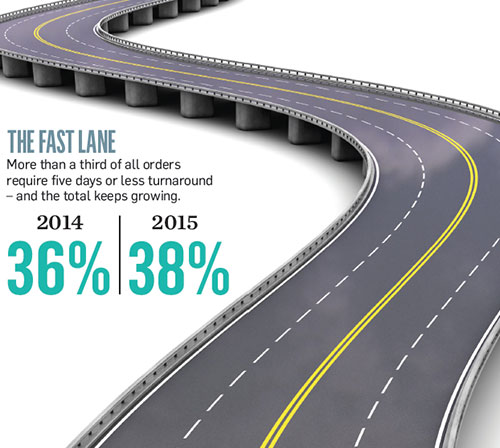

Perhaps the most significant result of this fast-paced mentality has been the increase in rush orders. Distributors report nearly four in 10 (38%) of their orders require turnaround of five days or less.

“Everybody wants everything tomorrow,” says Joel Kaplan, president of Specialties Inc. (asi/331340).

“Because of technology, clients are expecting more and more,” adds Harry Ein, owner of Perfection Promo, an affiliate of iPROMOTEu (asi/232119).

Large distributors had more rush orders than small and medium distributors, though the gap shrunk compared to the previous year. Why is it most common with larger distributors? “They handle more rush orders because they simply have the resources: art, availability and manpower,” says Brian Abrams, founder of Corporate Imaging Concepts (CIC, asi/168962), who reports that online orders account for 37% of CIC’s yearly business.

So what exactly are rush orders? Well, the definition varies depending on who you ask. Abrams says 24 hours or one business day. Ein says three to four days. Kaplan defines it as a week. “Twenty years ago, I would have answered four weeks,” Kaplan says. “Five years ago, I would have said two weeks.”

Although they disagree on the timeframe, the reality is still the same: fulfillment times for distributors are accelerating, straining their resources and forcing them to adapt to the immediacy of the modern age. Catering to the popularity of rush orders has been a challenge, they all agree.

Ein says Perfection Promo handles rush orders for major clients on a consistent basis, but those same orders might not be worth the hassle for accommodating a first-time customer. “Sometimes I’ll turn away a rush order if the risk is too great to get it done properly,” he says. “It’s more important to establish a trust with the client than attempting the order.”

The relationship between a distributor and client isn’t the only factor – the distributor must also choose a trustworthy supplier who can get the job done in time. Vendors who can hasten standard production at a moment’s notice are a distributor’s best friend, and more importantly, greatest asset when bidding for business. “We use suppliers who we trust can get the work done in time,” Kaplan says. “We don’t like to say no, so we go the extra mile and will do whatever it takes to get the order ready.”

The relationship between a distributor and client isn’t the only factor – the distributor must also choose a trustworthy supplier who can get the job done in time. Vendors who can hasten standard production at a moment’s notice are a distributor’s best friend, and more importantly, greatest asset when bidding for business. “We use suppliers who we trust can get the work done in time,” Kaplan says. “We don’t like to say no, so we go the extra mile and will do whatever it takes to get the order ready.”

The communication between distributor, supplier and customer becomes more important during rushes as compared to a standard order process. With the limited time crunch, distributors must relay the expectations and deadlines to the supplier, then transmit the factory’s response to the client, and then work with the supplier to have the order ready on time. “If the client waits four hours to approve the order, and the supplier’s cutoff is in two hours, we can’t possibly ship it in time,” Ein says. “Communication is everything.”

Should a distributor actively court rush order business? The approaches vary. In meetings and discussions with potential clients, Abrams doesn’t specifically mention rush orders because he says they’re now implied. “Service, creativity and efficiency should be part of every distributor’s sales pitch,” Abrams says.

On the other hand, Ein mentions that the company handles rush orders, but he says it’s not such a “wow” factor for customers as it was five or 10 years ago. “They’ve seen it done for other people,” he says. “They know it’s possible and they almost expect it.”

Kaplan disagrees about mentioning rush orders, arguing that distributors shouldn’t actively court them because it adds unnecessary stress on all parties involved. “We all have lives beyond our work and we try to strike that balance,” Kaplan says, going so far as to discourage clients from demanding a rapid turnaround.

Even though rush orders can command higher prices since clients aren’t as inclined to price shop, the margin for error is slimmer and the possibility of unhappy customers is significantly greater. “We try to educate our clients that rush orders isn’t the best way,” Kaplan adds. “When you’re rushing, you make mistakes and you only have time to catch them, not proof them.”

On the surface, rush orders aren’t the challenge, says Abrams. It’s what they represent: business infringing upon home life, around-the-clock availability and instant response to customers interrupting precious time with his wife and two daughters. “That’s the real challenge,” Abrams says.