May 17, 2017

Is It Time to Buy a Multi-Head Machine?

Before moving up to a multi-head embroidery machine, take some time to calculate which configuration will make your shop most efficient.

Are you spending more time sewing than sleeping? It’s nice to be busy, but if you can’t keep up with demand, it might be time to increase your production capacity. After all, you can only do so much on a single head. So what’s the right machine setup?

Are you spending more time sewing than sleeping? It’s nice to be busy, but if you can’t keep up with demand, it might be time to increase your production capacity. After all, you can only do so much on a single head. So what’s the right machine setup?

Because each embroidery business is different, production requirements will vary significantly from shop to shop, and it’s that criteria that will define the right machine or combination of machines needed to produce your orders efficiently and profitably. Bottom-line, a machine’s capability needs to be matched to a business’s requirements. Let’s take a closer look.

Assume that the average sewing job has 7,500 stitches and six colors. Running at a speed of 800 spm, and taking into account factors like speed variation, trims and color changes, the sew time works out to about 13 minutes. Removing a finished hooped garment from the machine and replacing it with a new one adds another minute or two, so assume about 15 minutes for each run.

Initially, it would seem that a single-head machine would produce four pieces per hour, a two-head machine eight pieces, a four-head machine 16 pieces, a six-head 24 pieces, and so on. But that’s only when you’re running the same job over and over. In reality, downtime is incurred every time a new job has to be set up. Such downtime includes changing thread, loading a design, programming needle sequences, changing the pantograph from tubular to caps, etc. The more heads, the longer the potential downtime. Thus, it’s usually not economical to use a multi-head machine for small runs, as you may spend more time setting up than sewing.

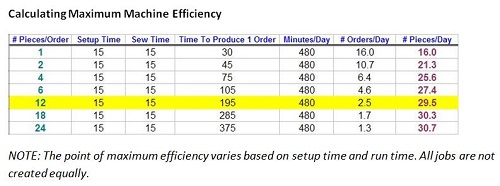

Every machine has a point of maximum efficiency, based on the machine’s capabilities as well as the parameters of the job. In the chart shown, it’s assumed that a single-head machine is being used and that every job is roughly the same run time. In addition, it’s assumed that the machine operator spends 15 minutes on setup.

As you can see, a 12-piece job is more productive than a series of one-piece jobs. However, after the 12-piece threshold, the increase in output drops off. This illustrates an important point: Every machine has a point of maximum efficiency, after which output plateaus.

As machines increase in size, the point of maximum efficiency increases as well, such that it is cheaper to do a large order on a large machine than it is to do the same order on a small machine. Here is a simple rule of thumb to give you a ballpark idea of the right number of heads for your shop. If your average sewing job is 5,000 to 7,500 stitches with five to eight color changes, then divide the number of pieces in an average order (assuming the same logo on each piece) by 12 to determine the best head configuration. For example, if your average order is 72 pieces of same thing, then a six-head is the ideal machine.

But just buying a larger machine may not be the right solution, as there is another angle to consider: How many jobs need to be produced simultaneously? While buying a larger machine increases your overall production capacity, it still only lets you sew one order at a time, when in many cases you need to be able to produce several orders at the same time. Thus, if you were considering a six-head machine, you should also look at the concept of three two-head machines or a four head and a two head, or maybe even six single-head machines. Multiple machines give you more versatility as you can produce more than one order at the same time or run the same order on all machines at once.

Since most manufacturers offer the ability to network multiple machines, you can get very creative in how you set up your machines. But with multiple small machines, there are certain limits. Production studies have shown that in most situations one person can only manage three single heads effectively. Thus, if you invested in six single heads, you would need two operators. In comparison, one person can easily manage a six-head machine alone.

Beyond head configuration, there are other things to consider. The first is thread. You will need one cone per color per head. Moving from a single head to a six head for a shop with a normal inventory of 100 colors is a big investment. Same goes for bobbins, bobbin cases, backing and needles. More heads equals more supplies.

And then there is hooping. With a single head, you only need to get the starting point of a garment close to the center of the hoop. Once the hoop is on the machine, you can make a final alignment using the pantograph movement keys. With a multi head, you have to hoop each item precisely because when you adjust the pantograph for one garment it affects all of them. Thus, if you don’t already have one, you will need to invest in a really good quality hooping device to ensure precision.

So, what’s the best setup? It’s all about how your orders break down and what’s most effective to manage your workload, while providing flexibility and versatility.

***

Jimmy Lamb is an award-winning author and international speaker with more than 25 years of experience in the apparel decoration business. Currently, he is the manager of communication at Sawgrass Technologies.