August 11, 2020

Duke Scientists Identify Which Masks Work Best

N95s performed the best, while fleece neck gaiters surprisingly created more respiratory droplets than wearing no mask at all.

Testing by researchers at Duke University of 14 popular mask styles has yielded new insights about which are the most effective at blocking respiratory droplets to help curb the spread of the coronavirus. Fitted N95s performed the best, and both three-layer surgical masks and cotton masks also did well.

Folded bandanas and knitted masks performed poorly in the tests. Fleece neck gaiters were the least effective type of face covering and actually resulted in a higher number of respiratory droplets because the material seemed to break down larger droplets into smaller particles that are more easily carried away by the air.

These are the types of masks Duke University researchers tested. N95s performed the best, but three-layer surgical masks and cotton masks also did well. Photo courtesy Emma Fischer, Duke University.

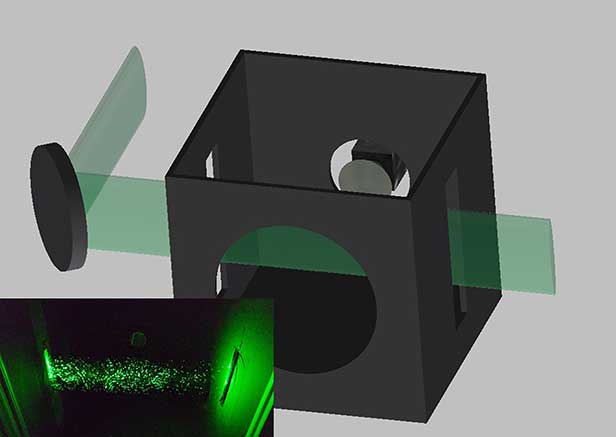

Researchers in Duke’s physics department created a relatively simple device to test the masks. The setup consisted of a box, a laser, a lens and a cellphone camera. They used the device to check for droplet emissions when a speaker wore no mask, then repeated the test when the speaker was wearing a mask. Each mask was tested 10 times. Martin Fischer, one of the authors of the study, explained to CNN how the device works: “The laser beam is expanded vertically to form a thin sheet of light, which we shine through slits on the left and right side of the box.”

Researchers at Duke University developed this inexpensive device to test the effectiveness of various types of mask. Photo courtesy Martin Fischer, Duke University.

A speaker can talk into a hole in the front of the box, and the cellphone camera is placed on the back of the box to record light that’s scattered in all directions by the respiratory droplets that cut through the laser beam when they talk. A computer algorithm then counts the number of droplets seen in the resulting video.

“We confirmed that when people speak, small droplets get expelled, so disease can be spread by talking, without coughing or sneezing,” said Fischer, director of Duke’s Advanced Light Imaging and Spectroscopy facility, in a press release from Duke Health.

The proof-of-concept study appeared online Friday, Aug. 7 in the journal Science Advances.

Fischer and other researchers created the test after being approached by Duke physician Eric Westman, one of the first champions of masking to help curtail the spread of the virus. Westman was working with a local nonprofit to provide free masks to at-risk and underserved populations in the greater Durham area and wanted to make sure the masks provided were actually effective and not just spreading a false sense of security.

The test developed by Fischer and his team is just a demonstration, and more work needs to be done to investigate all variables; however, Fischer believes it shows that tests like this could easily be done by businesses and other groups providing masks to employees and patrons. “We wanted to develop a simple, low-cost method that we could share with others in the community to encourage the testing of materials, mask prototypes and fittings,” Fischer said. “The parts for the test apparatus are accessible and easy to assemble, and we’ve shown that they can provide helpful information about the effectiveness of masking.”

In fact, information from the test has already been put to use. Westman and the “Cover Durham” initiative were trying to make a decision on a face covering to be purchased in volume and discovered that the masks they were about to buy were ineffective. “They were no good,” Westman said. “The notion that ‘anything is better than nothing’ didn’t hold true.” Still, the right kind of mask – whether an N95, surgical or cotton variety – is still a simple and easy way to reduce viral spread, Westman said. “If everyone wore a mask, we could stop up to 99% of these droplets before they reach someone else,” he added. “In the absence of a vaccine or antiviral medicine, it’s one proven way to protect others as well as yourself.”

Product Hub

Find the latest in quality products, must-know trends and fresh ideas for upcoming end-buyer campaigns.