When you buy a branded T-shirt from Oatly, there are a few things guaranteed. You can select your sizing and choose from a handful of catchphrases – proclaiming to the world that you’re a “weekend vegan” or that you’re part of the “post milk generation.” The price, sans shipping and taxes, is also front and center. What you won’t know until the merch arrives at your doorstep, though, is the color, print and style of the tee you ordered.

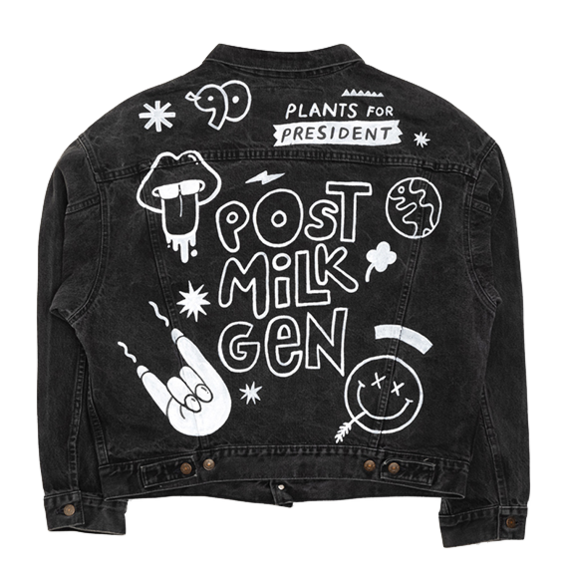

That’s because the trendy oat milk company partnered with online thrift store Goodfair to sell “Reruns” – upcycled pre-owned tees with new slogans and a tiny hem tag that reads discreetly, but nonetheless pointedly: “New merch is like the last thing the planet needs.” The brand has also done limited-edition merch drops with artists to “rescue and reimagine” vintage denim jackets and holiday sweaters into singular statement pieces.

Only 15% of household textiles are recycled in U.S. The rest ends up in landfills.

(SMART)

Saie, an upstart clean makeup brand founded in 2019, took a similar approach to the merch requests it started receiving shortly after launching. The company partnered with a handful of resale vendors to create a capsule collection of vintage duds, reworked to fit Saie’s aesthetic – slip dresses dyed in various shades of purple, sweatshirts embroidered with slogans “Feel Good” and “Keep Glowing” and denim jackets with the company name chainstitched above the pocket.

Are these brands outliers in the vast world of custom merch, or are they bellwethers? Consider these statistics: More than 40% of millennials and Gen Z consumers have shopped for secondhand apparel, shoes or accessories in the past 12 months, according to the 2021 Resale Report released by online thrift giant ThredUp. In 2020, the secondhand market reached $36 billion, per that same report.

This shift in spending is being driven by a reprioritizing that people went through during the pandemic. One in three consumers cares more about wearing sustainable apparel than they did before 2020, according to ThredUp research. And according to market research firm NPD Group, more than a third of consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable apparel.

Redwood Classics Apparel partnered with Preloved to create the Ashley scarf, made by combining two vintage flannel shirts.

Viral news reports about where low-quality fast fashion often ends up after being worn once or twice (namely, atop heaping landfills halfway across the world or as tangled tentacles clogging up beaches) have also played a role. In fact, 47% of consumers say they’re interested primarily in long-lasting quality products.

While it’s unlikely that every promo buyer will be inspired to follow the lead of brands like Oatly and Saie and hit up the local Goodwill for their next decorated-apparel order, many are increasingly concerned about sustainability throughout the whole lifecycle of a garment – from when and how it’s made and distributed to how long it’s worn to what happens once it’s reached the end of its original purpose.

“The traditional model is we take and we make and we waste it,” says Kathy Cheng, founder and president of Toronto-based Redwood Classics Apparel (asi/81627). “We’ve been working toward a reuse-based model. That’s the new model – approaching everyday life and business with a mindset of waste reduction.”

Clothing and household textiles make up 6.3% of the waste stream – equivalent to 81 pounds per person thrown away each year in the U.S.

(SMART)

Indeed, rethinking the greater purpose and lifespan of apparel is “the big challenge for promotional products,” says Emily Gigot, sustainability manager at SanMar (asi/84863), the largest supplier in the promo industry. “That’s our puzzle to solve: In what ways can we make product that could outlast an event?”

Instead of producing single-use styles, are there ways to make logos and decoration discreet so the garment isn’t tied to a particular time and place? Can it be designed as a cool and coveted keepsake the owner is proud to re-wear?

Saie, a clean beauty company, partnered with women-owned vintage vendors to create its merch collection. This pre-owned crewneck has an embroidered slogan across the front and the company name stitched on the back hip.

One surefire way to get end-user buy-in for a garment is by sourcing high-quality and brand-name gear that’s long-lasting. Even a few short years ago, the idea that people would be willing to pay more for premium promo T-shirts and fleece was a tough sell. But the conversation is changing. Andrew Graham, director of custom and wholesale at Marine Layer (asi/68730), remembers attending his first promo trade show in early 2017 and being met with a wall of skepticism at his company’s super-soft retail-brand tees made with low-impact and sustainable materials.

“Distributors were saying, ‘You’ll never sell a $15 shirt in this market. It will never happen,’” Graham recalls. Fast-forward to 2021, and Graham says he’s hearing a different tune. “The consistent refrain I hear is that Marine Layer is being requested. Instead of buying 1,500 [low-end] shirts, they’ll buy 500 and get more value out of them.

“What we’re seeing is a true shift to brand-name quality goods. It’s great for us, but I think it’s a good thing for the industry as a whole.”

Coming Full Circle

Suppliers have also been exploring ways to make the apparel production process more circular – keeping textiles out of landfills by breathing new life into cotton scraps from the cutting room floor or upcycling vintage fabrics into something completely new.

40% of millennials and Gen Z consumers have shopped for secondhand apparel in the past 12 months.

(ThredUp)

“As much as we want to be efficient with how we’re cutting pattern pieces for a new shirt, there’s always going to be scraps where there’s space in between,” Gigot says.

SanMar’s Re-Tee and Re-Fleece products are made of 100% recycled materials – a mix of post-consumer recycled polyester, recycled rayon and post-industrial recycled cotton. Marine Layer’s Re-Spun program allows consumers to send in their old T-shirts for store credit. Marine Layer sorts the garments and sends them to a partner facility in Spain to be converted back into yarn, which is then cut and sewn into a new shirt. Since the shirts are sorted by color before being turned into yarn, the process doesn’t involve dyeing or water usage, making it more sustainable than traditional apparel production. On its retail website, Marine Layer notes that it has diverted 250,000 tees from landfills and hopes to reach 350,000 by the end of 2022.

The supplier also offers the program to corporate partners, though it requires companies to commit to a buy-back percentage of new shirts created from the old or unusable garments they’ve donated. “In a perfect world, we would be able to take everything back, any misprint we’ll recycle no problem” Graham says. “Unfortunately, it’s too expensive to do that. The buyback keeps the circular production process in place.”

Oatly commissioned artists to upcycle vintage denim jackets as part of a limited-edition merch drop.

For several years now, Redwood Classics has been collaborating with Preloved, a company that rescues old clothing and upcycles it into something new. The companies have rescued landfill-bound wool sweaters and other vintage clothing and transformed them into face masks, winter scarves and mittens. One of their newest products, the Ashley scarf, is made from sewing together vintage flannels. “It’s 100% waste diversion,” Cheng says. “No virgin materials are being used, only vintage shirts.” Plus, she adds, each scarf is one-of-a-kind, though a logoed hem tag can be added for branding purposes.

What makes the scarves even more powerful is that for larger orders – at least 200 units – Redwood can quantify how much fabric has been diverted from a landfill, since the supplier is buying vintage textiles by the bale, paying by weight. “I think it’s quite unique,” Cheng says. “How many suppliers can actually say that and add that as value?”

42% of consumers say buying sustainable apparel is at least somewhat important.

(The NPD Group)

Working with vintage textiles can be labor intensive, requiring layers of processing. The Secondary Materials and Recycled Textiles (SMART) association estimates that the used clothing market is a roughly $1 billion industry. SMART members acquire byproducts from textile factories, and purchase excess textile donations from nonprofits, thrift stores and other sources. “SMART companies sort and grade the used clothing based on quality, condition and type,” according to the organization’s website. Once sorted, 45% of the items are reused as apparel, 30% are cut into wiping rags or polishing cloths used in commercial settings and 20% are reprocessed into basic fibers that become things like furniture stuffing, home insulation, carpet padding and other products. About 5% of the materials gathered are unusable – wet, moldy or otherwise contaminated – and are discarded, according to SMART.

“The traditional model is we take and we make and we waste it. We’ve been working toward a reuse-based model. That’s the new model.”Kathy Cheng, Redwood Classics Apparel

Once Redwood Classics receives a sorted bale of vintage textile, employees have to put it through further processing, looking at the items from a design perspective to choose the right colors, thickness or patterns. The fabric also requires special handling and cleaning, so it’s still using resources. But, “it’s less resource-intensive than handling virgin materials,” Cheng says.

Promo companies have also helped customers repurpose their own textile waste. For instance, Redwood Classics once took branded umbrellas that a client was going to throw away, turning the soft vinyl of the item into pillows and recycling the aluminum skeletons.

Oat milk brand Oatly upcycles pre-owned tees, adding new slogans, rather than creating brand-new merch.

SwagCycle, an environmentally focused promo venture that’s an outgrowth of Somerville, MA-based distributor Grossman Marketing Group (asi/215205), helps facilitate donation, upcycling and recycling of unwanted or outdated swag. As of October, the 2-year-old company has helped keep more than 330,000 items out of landfills and facilitated more than $800,000 worth of product donations to charitable causes.

According to founder Ben Grossman, SwagCycle is different from the “black box” clothing donation bins you see in strip mall parking lots because of its transparency. “We tell donors exactly where the products are going, the organization that’s taking them and exactly the purpose they’re being used for,” he says.

In Ghana’s Kantamanto Market, about 15 million pieces of clothing arrive from Western countries each week. About 40% ends up in landfills there.

(The OR Foundation)

Thanks to SwagCycle, extra T-shirts from a global tech company were donated to Greening Greenfield, a Massachusetts-based charity, which sponsored an event with the local 4-H club to cut and sew the tees, upcycling them into grocery totes. “That was a fun project to do,” Grossman says.

Of course, not all leftover swag is a good candidate for donations or even upcycling. Certain industries, like telecommunications or home health organizations for example, need to take old uniforms and branded apparel out of circulation to curb potential for impersonating one of their workers for nefarious purposes. And some swag is simply not built to last, so reuse – either through donation or upcycling – might not be a possibility. But as more businesses (and consumers) are educated about the concept of circular fashion, there’s more of an opportunity to consider a garment’s end-of-life plan before a single stitch is sewn.

In the past, corporate interest in sustainability has “gone in waves,” Grossman says. It was part of the conversation in the early aughts, then largely eschewed during the cost-cutting of the Great Recession. These days, despite economic pressures from the pandemic, “We’ve really seen a resurgence in demand for environmentally friendly products,” he says.

“It’s our perspective that sustainability isn’t going away,” Grossman adds. “We all have one planet; we have finite resources. It’s critically important to be good stewards of those resources to leave a better planet for the next generation than we have today.”