June 19, 2017

Border Battle

Could the U.S. and Mexico go from economic partners to commercial adversaries?

President Donald Trump built his campaign on being tough with Mexico. At his presidential campaign announcement speech in June 2015, he said, “When do we beat Mexico at the border? They’re laughing at us, at our stupidity. And now they’re beating us economically.”

Trump announced a plan to build a wall along the Mexico-U.S. border, finance this construction with a border adjustment tax on Mexican imports, renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and challenge manufacturers who plan to or currently manufacture goods in Mexico.

During his campaign, Trump surrogates like Peter Thiel cautioned to, “take him seriously, but not literally.” Thiel even said that the wall was more of a metaphor than a true policy position. However, this theory was too optimistic.

These policy changes have the potential to injure U.S. manufacturers. Approximately 60% of U.S.-Mexican trade is intra-firm, which means it will raise the cost of manufacturing in the United States. The bottom line is that any sort of tariff or tax will raise prices for consumers, as the costs associated with these measures are borne by consumers and not the targeted country.

The outlook for U.S.-Mexico relations and the ultimate effect on U.S. manufacturers and consumers remains unknown. So far, however, the impact has been negative and there is little indication that it will improve.

From Behemoth to Crisis

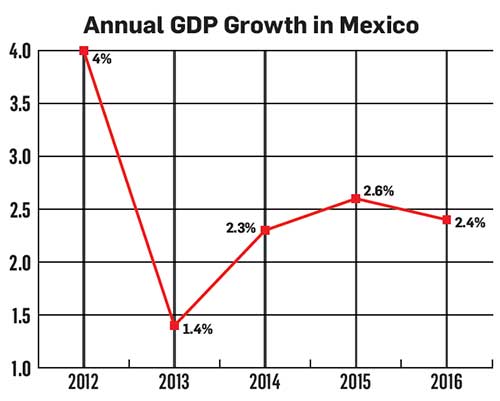

Mexico was facing a severe economic crisis even before Trump was elected. Its GDP expanded only 2.3% in 2016, a decline from the previous year. In response to rising oil prices, Mexico also deregulated its gasoline market, ending the country’s practice of subsidizing consumer purchases. This move has prompted widespread protests throughout the country, and has even resulted in calls for President Enrique Peña Nieto to resign. And the beleaguered Mexican peso, already facing downward pressures, continues to reach new lows against the U.S. dollar as concerns over Trump’s policies spook currency traders.

Did You Know?

Mexican exports to the U.S. increased from $73 billion in 1996 to $294 billion in 2016, a more than 300% rise.

Mexico has a long and established legacy as a global manufacturing superpower. In 1964, Volkswagen set up a plant in Puebla to manufacture Beetles, where more than 21 million autos were produced for domestic consumption and export to Europe before the factory was closed in 2003. And the manufacturing economy continued to blossom along the Mexico-U.S. border as auto, appliance and consumer electronics firms assembled and prepared goods for export to the U.S.

Additionally, Mexico has enjoyed an astronomical rise in trade, manufacturing and development since NAFTA went into effect in 1994. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, Mexican exports to the U.S. increased from $73 billion in 1996 to $294 billion in 2016, a more than 300% increase. Likewise, U.S. exports to Mexico have increased from $71.3 billion to $231 billion over the same period, a 224% increase.

Mexico has been growing into one of the world’s largest manufacturing countries. From 2008 to 2016, light vehicle production rose from 2.1 million to 3.6 million, making Mexico the fourth largest auto exporter after Germany, Japan and South Korea. And the global auto industry committed more than $23 billion in investment from 2013 to 2015. Companies like Toyota, Kia, BMW, General Motors, Ford, Audi, Volkswagen and others have all either made substantial investments or have announced plans to invest in capacity in Mexico.

The motivation and allure of doing business with Mexico is clear: its vicinity to the world’s largest automobile market as well as NAFTA to get them to market with little or no tariff impact. From this, manufacturers and suppliers formed integrated maquiladoras, closely knit manufacturing centers and abbreviated supply chains.

The impact of Trump’s election has reverberated throughout the Mexican economy. The peso has declined to a historic low against the U.S. dollar, settling at almost 20 to 1 in value. And Fitch Ratings issued a negative outlook for Mexico’s sovereign debt, and they have threatened to reduce their debt rating in response to the potential impact of Trump’s policies.

Trump Train Collides With NAFTA

In a White House statement, Trump said, “Blue collar towns and cities have watched their factories close and good-paying jobs move overseas, while Americans face a mounting trade deficit and a devastated manufacturing base.” Trump prioritized manufacturing and blue-collar workers during his campaign for president, which likely contributed to his victory. To achieve this goal, Trump has outlined a multifaceted approach to deregulate the Obama-era environmental and labor protections, reduce and simplify the corporate tax code, and tackle unfair trade agreements.

The first casualty of this protectionist movement was withdrawing from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which will likely cause the agreement to fail. In one of his first acts in office, on January 23, President Trump signed the executive order that officially withdrew the U.S. from the agreement. As a signatory, Mexico was expected to benefit considerably from this agreement. And while the withdrawal of the USA from the agreement does not kill it, the competing Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) Agreement will likely supplant it as the next Pacific region trade regime.

Trump has also targeted NAFTA. He has blamed it for the loss of manufacturing jobs, as capacity has shifted from the U.S. to Mexico. In a tweet from October, Trump proclaimed that as president he would, “renegotiate NAFTA. If I can’t make a great deal, we’re going to tear it up. We’re going to get this economy running again.”

He signed another executive order on January 23, invoking NAFTA Article 2206, which withdraws the U.S. from NAFTA after six months. The presumption is that Trump will renegotiate the agreement, but the administration has not offered any substantive guidance as to how it will do so. For example, the U.S. could negotiate two separate, bilateral agreements with Canada and Mexico. However, the results of a lapse in agreements could be devastating, as 80% of Mexico’s exports and 75% of Canada’s exports end up in the United States.

Contrary to Trump’s assertions, NAFTA has been a considerable boon to the U.S. workforce. According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, NAFTA supports 14 million jobs, which means tens to hundreds of thousands of jobs in every state. And five million of those jobs are directly supported by trade with Mexico. And Mexican firms further employ another 127,000 workers at the sites in the U.S. Small and medium-sized enterprises are the biggest users of NAFTA, with 126,000 firms selling goods and services to Canada and Mexico.

The Trump administration has made it clear that Canada is not the target of the NAFTA renegotiation. According to one Trump adviser, Stephen Schwarzman, at an address to several Canadian officials, “Canada is very well-positioned for any discussions with the United States,” and reiterated the White House position that Canada will not be hit hard by any changes the U.S. seeks to make to NAFTA.

Mexico is taking a hard line during the renegotiations with the U.S. and in response to Trump. Ildefonso Guajardo Villarreal, Mexico’s secretary of the economy, has said that Mexico is prepared to leave NAFTA if negotiations with the USA didn’t go well. During an interview, the incumbent secretary said, “If we are going to go for something that is less than what we have, it makes no sense to stay.” And Mexico carries significant leverage: they could easily target U.S. agriculture imports, which would harm the politically important U.S. corn farmers, as 28% of U.S. corn exports go to Mexico.

In addition to retaliatory actions by Mexico targeting the U.S. agriculture sector, this looming trade war has broader implications for the U.S. economy. Approximately 60% of all imports from Canada and Mexico are inputs into U.S. manufacturing, some of which is consumed by the domestic economy. Therefore, any increase in the cost of trading with Mexico will be passed onto consumers through higher prices or lower availability.

Encouraging Reshoring From Mexico

One of President Trump’s most memorable campaign tactics was to harshly target domestic firms that have moved manufacturing from the U.S. to Mexico. It began with an attack on Carrier Corporation for its decision to shift some manufacturing output from Indiana to Mexico, thereby eliminating more than 1,200 jobs. Trump threatened to levy a 45% tax on all Carrier imports into the U.S. “I don’t want them moving out of the country without consequences,” he said at a press conference in December. Carrier responded by changing strategy, reducing the number of jobs it was outsourcing to 400, and preserving the manufacturing facility. However, it came at a high cost, with Indiana being forced to grant significant tax concessions.

Trump has utilized this strategy with more than a dozen domestic and foreign companies, with an emphasis on the automotive sector. One of the highest profile targets was Ford. Trump targeted Ford for its $1.6 billion plant in San Luis Potosi that was going to manufacture smaller cars for the U.S. market. After being singled out, Ford abandoned its plans to open the plant, but continued to manufacture the Focus at another existing Mexican facility for the U.S. market. Ford denied that Trump played a role in this decision, but rather it was based on other business decisions. Ford also announced that it would be investing a further $800 million in the U.S.

Several companies who have not abandoned their plans have been forced to publicly justify their decision. Audi, Volkswagen, BMW, General Motors, Fiat, Chrysler and Toyota have all been specifically targeted by Trump, usually via tweet. Fiat Chrysler responded that it would move manufacturing back to the U.S. if “properly motivated.” BMW defended its decision by pointing to its facility in South Carolina, which is the largest in the world. And they’re investing an additional $1 billion in its existing facility in North Carolina, further cementing its dedication to U.S. manufacturing.

Other industries are shifting their international supply chain patterns in response to Trump’s policies. South Korean electronics giant LG currently has three facilities in Mexico. However, they announced in February that they would be investing more than $250 million in a U.S. facility in response to Trump’s statements. Likewise, Samsung announced in March 2017 that it would shift some capacity from Mexico to the USA due to the changing political climate.

But make no mistake: Manufacturing in Mexico is not going to completely disappear. Mexico has a robust trade regime with the European Union and will continue to manufacture for those markets. For example, BMW will continue to expand capacity for its 3-Series model for the EU market. Even if their exports to the U.S. decline, they can continue to send output to Europe. In addition, Mexico is an important factor in the automotive manufacturing supply chain and it continues to be a cost-effective strategy to minimize price for consumers.

What’s Next for the U.S. & Mexico?

President Trump has called into question some of the U.S’s relationships with its strongest political and economic allies. Recently, the U.K. was scapegoated by the White House in an unsubstantiated wiretapping claim, angering one of its oldest allies. Germany’s Angela Merkel has had a volatile relationship with Trump, which was highlighted by their recent meeting at the White House. Trump reportedly hung up on the Prime Minister of Australia during a discussion about refugees. And Mexico’s President Enrique Peña Nieto and Trump have traded barbs over Twitter and through more official diplomatic channels.

This uncertainty limits the predictability of how the relationship between the U.S. and Mexico will evolve. Production is slowly shifting from Mexico to the USA in response to some of the direct threats Trump makes.

The U.S. strategy in Mexico will remain unclear until NAFTA is renegotiated and executed. That will articulate what businesses can expect by engaging in trade and commerce with Mexico. However, until a strategy has been more clearly conveyed, companies risk negative presidential tweets, being forced to explain why they haven’t converted all manufacturing capacity to the United States, and will have to navigate how to address financial threats.

– Email: patrickwgleeson@gmail.com