March 27, 2017

Eye on China

Will 2017 usher in a trade war between the world’s two largest economies?

The United States and China are on an economic collision course. Years of accusations of trade agreement violations and perceived unfair practices have chilled a once hopeful alliance. President Donald Trump has targeted this unfair treatment as one of the primary threats to the U.S. economy. In achieving his campaign promise to “Make America Great Again,” he has outlined an aggressive strategy to strengthen the United States’ negotiating position with China.

China joined the modern global trade regime in 2001, when then President Bill Clinton supported its membership to the World Trade Organization as a non-market economy, an important distinction for the coming trade battles between them and the rest of the world. Later, President George W. Bush granted China Permanent Normal Trading Relations (PNTR), which further legitimized their role.

China has been undergoing a tremendous economic transformation. It’s transitioning away from its role as a low-cost, low value-added manufacturing country into a global economic behemoth. The centerpiece of this reform is the China 2025 initiative, which is a multifaceted approach to cultivate new industries and to make China the foremost engineering and manufacturing country in the world. China is also leading the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which is replacing the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as the primary Asia free trade agreement.

The future of Sino-U.S. relations remains completely unpredictable. President Trump’s policy proposals and cabinet choices portend potentially significant economic and military challenges between the world’s two largest economies. This could create serious uncertainty and disruption in global supply chains and force companies and sectors – including the promo products industry – to reconsider how they source even basic materials.

China’s Economic Uncertainty

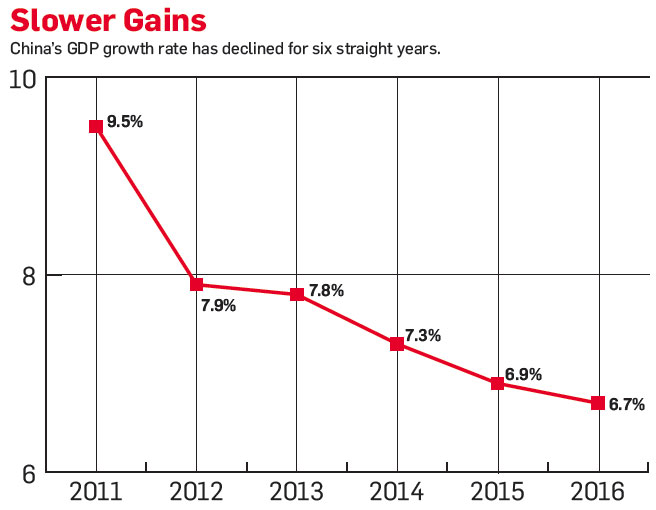

China’s current economic position remains unstable, but improving. After a challenging period in 2015 and 2016, key economic indicators have ticked higher. The China Caixin PMI, which is an important indicator measuring the health of the manufacturing sector, rose to 51.9 in December, which is its highest level since 2013. And while manufacturing output has declined, China did achieve 6.7% GDP growth in 2016.

China also continues to be the dominant global trading partner. According to recent trade data, China is the largest trading partner for 124 different countries. Meanwhile the United States is the largest with only 56 countries. Despite its dominance, Chinese exports declined 7.7% in 2016, its worst annual change since the global economic crisis in 2009. The primary cause for this decline is its eroding competitiveness with low-wage countries. And China does not expect its trade to recover in 2017.

These indicators are part of a tectonic shift in China’s economy. Built up on its reputation for low-cost labor, China has experienced rising costs, which is forcing labor-intensive industries to move to Vietnam, Cambodia, India, Malaysia and East Africa. In fact, according to the World Bank’s report “Stitches to Riches,” this shift in manufacturing capacity is expected to create more than 1.5 million jobs in the textile and apparel sectors alone.

China is responding with an ambitious initiative: China 2025. This plan is the first step in achieving its ultimate goal of being the world’s dominant economy in 2049, which is a symbolically important date 100 years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Through targeted state policies, the plan will cultivate sectors such as green energy, robotics, and medical devices.

Is RCEP the New TPP?

Trump signed an executive order on January 23, 2017, formally ending the United States’ participation in the TPP. “We’ve been talking about it for a long time. Great thing for the American worker,” he said as he held up one of his first orders as president. After almost 10 years of negotiations between 12 Pacific countries covering everything from tariffs, the environment and labor rights, the TPP became politically toxic as both Democrats and Republicans joined forces to oppose the monumental trade agreement. In addition to excluding China, it allowed the U.S. and its allies to write the rules for the next generation of high-quality, multilateral trade agreements.

With the United States formally exited from the TPP, the RCEP has ascended as the dominant regional agreement. Led by China, the agreement includes the 10 ASEAN countries, Australia, India, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea. Two other TPP countries, Peru and Chile, have also expressed considerable interest in joining negotiations following the decline of the alternative. And the TPP could even continue with China as a partner. Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said “there is also the opportunity for the TPP to proceed without the United States. Certainly there is the potential for China to join the TPP.”

While the long-term effects of the fall of the TPP and the rise of the RCEP are unknown, it does weaken the United States’ position and economic goals. It endows China with considerable power to control trade in the world’s fastest growing region, which ultimately runs contrary to Trump’s ambitions to strengthen the USA’s negotiating position against China. And by excluding the United States, it prevents U.S.-based companies from accessing this region with a preferential trade status. Ultimately, many analysts believe this shift from the TPP to the RCEP will have a negative impact on the U.S. economy.

Complaints Against China

China has been the target of complaints by governments and companies since joining the WTO. China supports and promotes national champions and its state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Central planners have supported sectors such as steel, aluminum, manufacturing, raw materials, and banking with preferential loans, favorable policies, and subsidized inputs. As a result, the U.S. Department of Commerce has continued to hit China with antidumping and countervailing duties on goods like steel in response.

There have also been complaints that Chinese enforcement agencies and authorities discriminate against foreign companies operating in China. Faced with everything from forced technology transfers and local content requirements, foreign companies continue to deal with considerable obstacles if they seek to do business in China. While disparate treatment has been common, the forced re-merger of several large manufacturing companies to create global champions accentuates China’s favoritism of domestic firms in applying regulations like the antimonopoly laws.

Additionally, China continues to face criticism for its intervention in the currency market. In August 2015, China engaged in a significant intervention to devalue the RMB, which inspired strong rebukes from Congress. However, President Obama and the U.S. Treasury did not respond with any retaliatory measures. In fact, the U.S. Trade Representative refused to include currency manipulation in any of its negotiations, deferring to Congress and the U.S. Treasury to enact and enforce manipulation bans.

There are several broader political and geopolitical issues that the United States has confronted China about as well. China has had an expansive policy of claiming islands throughout the South China Seas, most notably laying claim to the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands in an ongoing territorial dispute with Japan. China is also building islands throughout the South China Sea, fortifying them with landing strips and military bases, and further securing its role as the preeminent force in Asia.

Not to be forgotten is this reality: the United States is in a precarious negotiating position with China. According to the U.S. Treasury, China currently owns 8.7% of U.S. debt, which makes it the United States’ largest foreign creditor. In fact, the Chinese own 30% of all U.S. debt held by other countries. And while China has not indicated it will significantly change its position, it provides them with considerable negotiating leverage with the United States.

Saber Rattling

Donald Trump ran his campaign on the promise to “Make America Great Again” and to bring back manufacturing jobs to the U.S. And while he is correct in saying that manufacturing employment is down, from 19 million in 1980 to 12 million today, manufacturing output has more than tripled in that time. In the new president’s effort to bring back manufacturing jobs, he has promised to be tough on China and aggressively negotiate for fair trade.

One of the president’s proposals is to impose a tariff ranging from 35%-45% on Chinese imports. This proposition appears fraught with risk. China would be within its legal authority to bring a case before the World Trade Organization’s Dispute Settlement Body. This would allow the Chinese to seek legal retribution and compensation for harm to their export industries. In addition, the tariff would likely cause more harm to the United States than to China. For example, according to a Peterson Institute for International Economics report, a 2011 tariff on Chinese tire imports had a net negative impact on the U.S. economy. Initially, the tariff created approximately 1,200 new jobs because U.S. consumers purchased domestic rather than Chinese tires. However, consumers paid an additional $1.1 billion, which essentially cost consumers more than $900,000 per job saved. And China retaliated with tariffs on U.S. chicken exports, which cost U.S. farmers $1 billion.

And perhaps inadvertently, Trump has antagonized U.S. relations with China following his victory in November when he had a conversation with Taiwanese President Tai Ing-wen. For a time, this act directly called into question the U.S.’s commitment to the “one China” policy that was established when the U.S. first recognized the PRC. Further inflaming relations, Trump stated in a recent television interview that he did not feel “bound by a one-China policy unless we make a deal with China having to do with other things, including trade.” It was only later, in a February call with China President Xi Jinping, that Trump said the U.S. will honor the long-standing diplomatic policy.

But everything wasn’t perfectly smoothed over. Trump has still chastised China for its failure to reign in North Korea. Via Tweet, Trump said “China has been taking out massive amounts of money & wealth from the U.S. in totally one-sided trade, but won’t help with North Korea. Nice!” While it’s true that China has failed to intervene in North Korea’s nuclear program and human rights abuses, China considers North Korea within its sphere of influence, and any U.S. interference in that relationship will further erode Sino-U.S. relations.

The Anti-China Cabinet

Unquestionably, Trump’s slate of cabinet members are anti-China. Most notably, Professor Peter Navarro has been tapped to lead the newly formed National Trade Council, which will coordinate trade policy at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative and Department of Commerce. Navarro, a self-described “Trump Democrat,” blames China for the past 15 years of stagnated wages and job losses in manufacturing. Citing first-hand accounts of his MBA students at the University of California, Irvine, he observed the direct impact of what he calls illegal export subsidies and currency manipulation.

President Trump asked Ambassador Robert Lighthizer to serve as U.S. Trade Representative. Previously a partner at international law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, Lighthizer is a former deputy trade representative from the Reagan administration. He has been a long-time opponent of unbridled free trade. In 2008, he questioned John McCain’s commitment to conservative policies due to his proposed free trade agenda. In a 2008 op-ed in The New York Times, he wrote, “Many American conservatives have opposed free trade. Jesse Helms, the most outspoken conservative in the Senate for three decades, was no free trader. Neither was Alexander Hamilton, who could be considered the founder of American conservatism.”

Lighthizer is also a staunch critic of China. At a 2010 Congressional hearing, he stated, “Years of passivity and drift among U.S. policymakers have allowed the U.S.-China trade deficit to grow to the point where it is widely recognized as a major threat to our economy. Going forward, U.S. policymakers should take these problems more seriously, and should take a much more aggressive approach in dealing with China.” Lighthizer is expected to bring these nationalistic trade views and attitudes towards China to his new role.

Trump picked billionaire businessman Wilbur Ross for the position of Secretary of Commerce. Ross is the former CEO of International Steel, where he lobbied for steel tariffs in 2002 from the Bush Administration’s International Trade Commission. And while Ross is a former free trade advocate and signed a letter of support for the TPP, his hardline stance on the use of tariffs, duties and other defensive trade remedies will make him one of the most anti-China secretaries of commerce.

And finally, the president chose Rex Tillerson, the former chairman and CEO of ExxonMobil, for Secretary of State. Tillerson has said that China’s influence in the South China Sea has grown too strong and that their island-building needs to be restrained. At his confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill, he said that, “We’re going to have to send China a clear signal that, first, the island-building stops. And second, your access to those islands also is not going to be allowed.” China’s response has been swift and strong. In a recent op-ed, the China Daily responded, “Such remarks are not worth taking seriously because they are a mish-mash of naivety, shortsightedness, worn-out prejudices and unrealistic political fantasies. Should he act on them in the real world, it would be disastrous.”

China’s Top Trade Partners By Exports

United States: $411 billion (18% of total China exports)

Hong Kong: $334 billion (14.6%)

Japan: $136 billion (6%)

South Korea: $102 billion (4.4%)

Germany: $69 billion (3%)

Vietnam: $66 billion (2.9%)

United Kingdom: $60 billion (2.6%)

Netherlands: $60 billion (2.6%)

India: $58 billion (2.6%)

Singapore: $53 billion (2.3%)

What’s Next?

China and the U.S. are on the precipice of a potentially dangerous trade war. President Trump has drawn a hard line, demanding a broad renegotiation of the status quo. And he has fortified these positions by installing some anti-China cabinet members who will steer the foreign trade policy agenda.

It seems unfair to blame China exclusively for recent outcomes. Many of the jobs that China has been accused of “stealing” have long since left China’s factories for even lower wage countries in Southeast Asia and East Africa. And U.S. manufacturing employment has fallen due to automation.

The only certainty about the future of Sino-U.S. relations is that it’s going through a recalibration. Whether President Trump’s negotiating team secures concessions on issues like currency manipulation and state support of SOEs or engages in a crippling economic trade war or even clashes on the South China Sea, the U.S. is rapidly entering a new stage of its relationship with China. And companies operating in or sourcing from China could well be required to recalibrate their supply chains in response to any punitive action from the Trump Administration – before it’s too late.

– Email: patrick.w.gleeson@gmail.com