April 20, 2016

The Essential Role Of Promotional Products in Politics

Investing millions in promotional products helped fuel the unexpected rise of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders – and reinforced promo’s essential role in the race for our nation’s highest office.

Two political outsiders – one a successful businessman, the other a long-time independent – run for office. The former’s presence in the race is regarded as an open act of ego stroking and instant fodder for the media circus. The latter is a virtual unknown among large blocks of voters, and someone so lightly regarded that his main opponent won’t even mention his name. And yet, through concerted marketing efforts that include savvy messaging and a heavy investment in promotional products, both wildly surpass expectations. The businessman is the unexpected party front runner. The now-former independent has become a surprisingly formidable opponent.

So how much credit do promotional products deserve for the astonishing election success of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders? More than you might think.

In this funhouse mirror of a presidential election, candidate promotional items were warped into one of the notable curiosities. Most prominently, media outlets took note last fall of Trump’s substantial spending on hats, a pervasive branding blitz that turned the business mogul’s “Make America Great Again” ball caps into a cultural conversation piece.

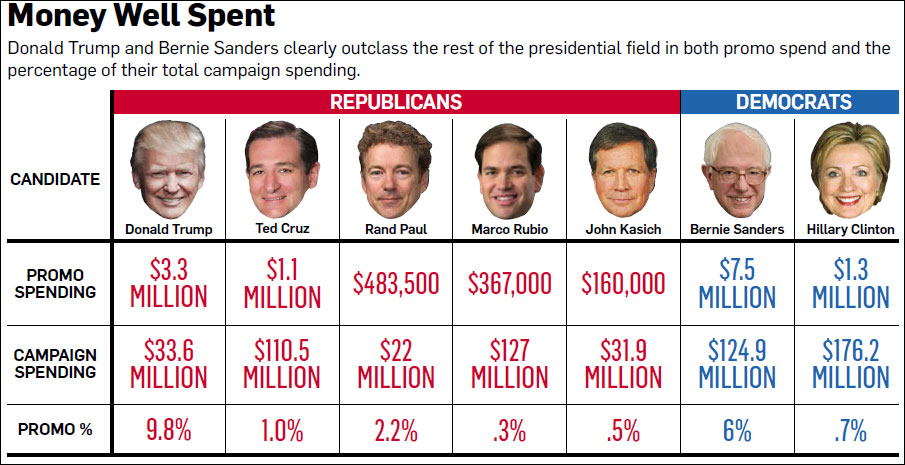

Yet even as the conversation shifted to election results and delegate counts, candidates like Trump and Sanders have continued their rampant spending on “collateral” (the term used by campaigns and political insiders). Through February’s primaries, Trump has spent $3.3 million, accounting for 9.8% of his total campaign spending. Sanders spent a blazing $7.5 million on promotional products, which makes up 6% of his total spending.

>> Marketing Lessons From the Presidential Election

>> How One Distributor Became Trump's Go-To Iowa Promo Firm

Other top candidates haven’t exactly penny-pinched on promo items: Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton has spent $1.3 million through February, and top Republican challenger Ted Cruz spent $1.1 million. But as financial figures from the campaign show (see chart), the proportion of their investment pales greatly compared to Trump and Sanders.

Even if neither candidate wins their party’s nomination, Trump and Sanders will still be regarded as the surprise successes of this election – accomplishments that champions of promotional products can confidently point to.

“A lot of political consultants will discourage candidates from buying collateral and say it’s a waste of money,” says Steve Grubbs, co-founder of Victorystore.com (asi/352041) and a longtime political strategist who most recently served as Iowa chief strategist for Rand Paul’s presidential campaign. “I say to them that yes, there are higher priorities, but if you use it wisely, collateral can help you win an election. And I think Trump and Sanders have made that case.”

Each candidate invested heavily in collateral from the earliest stages of their campaigns. Trump spent more on hats and branded items from July through September last year (a total of $910,000) than any other part of his campaign – a tidbit that gained national headlines. But so did Sanders, who in the same period of time spent over $3 million on “campaign paraphernalia.” Since then, Sanders has continued to pay well for promo items, but has also poured in staggering amounts of money into digital and television advertising. Meanwhile, Trump continues to run a unique campaign, perpetuating his significant reliance on promo while skimping on fields like polling, TV advertising and even campaign staffing – categories that candidates historically have lavished millions on.

How have those strategies paid off? In Sanders’ case, the Democrat has built a fundraising behemoth ($20 million in January, $43 million in February and another $44 million in March), fueled by millions of small donations from supporters. The Vermont Senator actively initiated this large-scale political Kickstarter; after all, the reminder on his website says that the campaign is “Paid For By Bernie 2016 (not the billionaires).” Sanders’ digital engagement receives a lion’s share of the credit, but his campaign’s promotional outreach is not only intertwined with that approach, but offers a tangible reward that would otherwise be lost on Super PACs and mega-donors.

Trump, on the other hand, has received very little donor money while funding the majority of his campaign from his vast coffers. His spending is a mere shadow of what other candidates have dropped; Trump’s $33.6 million is between a fifth and a quarter of what Hillary and Sanders have spent each. It’s a remarkable break from tradition, where the candidate with the most campaign money wins nine out of 10 times, and radical enough that many political experts still wonder whether Trump’s lean campaign will still lead to his demise.

Trump, on the other hand, has received very little donor money while funding the majority of his campaign from his vast coffers. His spending is a mere shadow of what other candidates have dropped; Trump’s $33.6 million is between a fifth and a quarter of what Hillary and Sanders have spent each. It’s a remarkable break from tradition, where the candidate with the most campaign money wins nine out of 10 times, and radical enough that many political experts still wonder whether Trump’s lean campaign will still lead to his demise.

Trump certainly has the financial means to spend his opponents into oblivion, but he’s refrained from doing so. So how is he leading? For starters, his celebrity aura and instant name recognition gave him an immediate advantage that he’s exploited mercilessly. His controversial statements and endlessly quotable tweets have cast a siren’s spell on the media. While Trump has spent just $10 million on paid advertising through February (outspent by five other Republican candidates), he has earned $1.9 billion worth of “free advertising” through media coverage – more than two and a half times what Clinton has earned.

“Whatever you think of Trump, it’s hard not to consider him a master marketer,” says Chris Russell, a New Jersey political consultant and strategist that has worked on a large number of congressional and state legislature campaigns. “He understands how to get himself front and center in the media. He understands how to control media cycles.”

And he has certainly put that marketing acumen to use. What item did he wear in a battery of appearances as hundreds of media camera eyes were trained on him? A red ballcap, produced by LA-based distributor Ace Specialties (asi/103533) that reads “Make America Great Again.” By August, searches for the Trump slogan ramped up and periodically spiked throughout the fall. “The hat became an iconic thing representing him because he had it on all the time,” says Meaghan Burdick, the director of marketing and merchandise for President Barack Obama’s presidential campaigns. And even though Trump retired the hat from public appearances from November to January and has worn it sparingly since, the message has stuck; searches for the slogan peaked by late February as Trump began winning primaries.

Click on image above for larger view of graphic

Click on image above for larger view of graphic

In the case of both candidates, their actions and impressive commitment to promotional products have helped to strike a nerve. Each has captured a fervent base of supporters that feel maligned, overlooked and previously unspoken for. Devotees of all candidates won’t hesitate to show their support through apparel and yard signs, but owners of Trump and Sanders gear appear to carry a special badge of pride – an open acknowledgement of their outsider leanings. Promotional products have emboldened them to express their feelings. “[Trump supporters] don’t want to be part of the Washington establishment,” says Dave McNeer, owner of Maxim Advertising, a Newton, IA-based distributor that has produced knit hats and other promotional items for Trump during the election. “And boy, if you’re wearing a Trump cap or a Trump T-shirt, you’re telling people that.”

Barack Obama became president under the banner of “Hope and Change,” and at least one thing proved indisputably true about those promises – the president’s victorious efforts in 2008 and 2012 completely redefined modern campaigning.

Many of the elements were plainly visible. The visual accoutrements of the Obama campaign – the now-iconic poster by street artist Shepard Fairey, the all-encapsulating “O” logo – exponentially raised the bar on how presidential candidates incorporated graphic design and creative branding. (Unsurprisingly, a cavalcade of logos was unleashed at the beginning of this election.) Also, the president’s complete embrace of digital and social media (just one example from 2008: Obama had 25 times more Twitter followers than John McCain) heralded a fundamental shift in the way that candidates and elected officials could win over voters.

Other strategies were less discernible but equally instrumental. The Obama campaign’s curation and use of databases (first started years before Obama’s presidential run) was light years ahead of other candidates. Four years later, the campaign shepherded a massive big data effort to segment voters into targeted groups and find their hidden motivators. The results were transformative. Political campaigns had always been marketing campaigns under a different guise, but now they were customized and personalized – “not mass marketing like all political campaigns had been in the past,” says Dr. Lisa Spiller, a professor of marketing at Christopher Newport University and the author of Branding the Candidate: Marketing Strategies to Win Your Vote. Summing up Obama’s strategies in total, Spiller says, “Never before in American political history has any candidate used so many of the modern marketing techniques that we have.”

These crucial strategies were also applied to his official promotional products. Traditionally in past elections, purchased merchandise (not including free giveaways at campaign stops) was simply a transactional exchange – the buyers a mystery to the campaign even as they ardently waved signs and wore shirts at the candidate’s rally. Obama for America, by contrast, devised a trackable system that registered every person who purchased an Obama item.

The information was invaluable. It allowed the campaign to mobilize supporters by persistently following up with encouragements to volunteer and donate. It offered crucial access to data to help create increasingly specific marketing messages. And it allowed the money from the purchases to be funneled directly to the campaign as direct contributions. (If the Obama campaign wasn’t the first to do this, it was certainly the first on such a immense scale). “We knew it was radically different from what had been done previously,” says Burdick, who has spent 15 years as a successful political fundraiser and marketer. All told, sales of promotional merchandise raised nearly $77 million for the Obama campaign — $37 million in 2008 and nearly $40 million four years later.

The campaign also constructed a robust loyalty program that utilized promotional products to motivate volunteers. Housed under my.barackobama.com (and often called MyBO for short), the network would award points for a variety of efforts (posting yard signs, writing blogs, etc.), and reward members with merchandise as they reached certain tiers. According to Spiller, MyBO members would also be entered into special drawings like front-row seats at an Obama rally. As Spiller and her co-author Jeff Bergner write in their book, members were ranked against each other “and a spirit of friendly competition ignited to see which members were making the greatest difference for Obama’s campaign.” All told, 70,000 MyBO fundraising pages generated more than $35 million for the campaign.

The design of the promotional products themselves began to change as well. Departing from the typical array of boxy cuts and static design, Obama’s apparel offerings featured a contemporary look and feel with specific tailored cuts for women and children. And the campaign wasn’t afraid to take creative gambles, such as fashion pieces designed by high-end designers that were priced well above typical political merch. “We pushed the limits of what we could do because he had more of a celebrity-like following,” Burdick says.

Not surprisingly, the Obama for America campaign spent freely on promotional products to execute these strategies. In 2012, it paid more than $6.7 million on campaign store merchandise, four times as much as Republican opponent Mitt Romney.

This wholehearted embrace of promotional products was very different from the complicated feelings many campaigns have about the medium. While rally giveaways and merchandise offerings are viewed as essential, strategists are typically skeptical over their effectiveness at reaching new voters. A study last year about yard signs helped to shed light. The authors found that candidate yard signs increased voter share by 1.7% on average – not a massive influence, but certainly enough to swing a close election. “We were surprised by these findings,” Alex Coppock, one of the co-authors of the study, told Politico, “because the conventional wisdom is that lawn signs don’t do much — they’re supposed to be a waste of money and time. Many campaign consultants think that signs ‘preach to the choir’ and not much else.”

Judging by this year’s offerings, many candidates are singing a different tune. Hillary Clinton’s store features a healthy variety of fashionable and customized apparel, including segmented offerings (Granite Staters for Hillary, Latinos for Hillary) and a “Made for History” collection of T-shirts from big-name designers. (One such shirt reads “Love Trumps Hate.”) Rainbow-hued pride offerings are available on both Clinton and Sanders’ stores. Rand Paul’s store, run by Grubbs and Victory Store, not only features a startling amount of variety (beer steins, bag toss games, headphones, autographed Constitutions), but also edgy fare (a T-shirt to protest sex trafficking) and humorous items (a shirt that reads “Don’t Drone Me, Bro!”).

This rash of creativity isn't just a result of greater belief in promotional products. Just as important, the arrival of digital printing and on-demand fulfillment removed the barriers that stunted creativity. According to Grubbs, campaigns previously would have to buy 500 shirts at a time and run up inventory; once the election was over, the losing candidates would dump their excess inventory in the landfill. “That was a bad system,” Grubbs admits. “It cost the campaigns money and it created a lot of waste.”

With digital capabilities, Grubbs says, “It allows us to be a lot more creative and do crazy things that were never possible before.” That’s exceedingly important in high-profile elections. At the local level, promotional products simply need to drive name recognition; a familiar name may easily be the deciding factor when someone casts a vote for town supervisor.

But as the campaign air gets more rarified – state legislature, congressional, presidential – and simple name identification alone becomes devalued, promotional items must drive a message. Last year during Paul’s presidential bid, his campaign conceived and sold “Hillary Hard Drives” that played off of Clinton’s email scandal. Victory Store purchased old busted hard drives, printed a funny label and sold them each for a $100 contribution. And as developments during the election occur, candidates now have the wherewithal to capitalize on instant controversy. Locked in a protracted fight with Trump, Ted Cruz’s campaign capitalized on the scrutiny of Trump University with shirts that read “I Applied to Trump University … And All I Got Was This T-Shirt.” Millions of buyers and recipients of campaign gear feel differently.

Presidential branding is as old as the rings of the hickory trees that symbolized the toughness of Andrew Jackson. Inventive promotional products have centuries-long roots too; those same trees were felled, carved and then doled out as brooms, sticks and poles to rouse voter support for “Old Hickory.” The need for a message is nothing new.

In the most recent presidential elections, digital technology and social media have completely altered the dynamics. Voter attention has widened but also narrowed, becoming more cognizant of the latest “controversy,” but less concerned with the nuts and bolts of policy. The media, too, has picked up on that shift and catered to the demand. Russell recalls working with a candidate who put together a detailed plan for economic growth. “He couldn’t get anyone to cover it with any kind of depth, because they didn’t have the time,” Russell says.

As a result, campaign messaging has become increasingly focused and simplistic. Dr. Jennifer Lees-Marshment says that candidates have honed in on just a couple key policies because any more will cause voters to “switch off.” And by carrying them in a single overriding message – “Hope and Change,” “Make America Great Again” – it gives voters a digestible idea to easily latch onto. “It’s a slogan, but it’s more than that – a sense of what the candidate and the product and the policy are all together,” says Lees-Marshment, an associate professor of politics at The University of Auckland in New Zealand and author and editor of 13 books. “The idea is that in this very clustered media environment, if you want to reach people, you got to have something they can understand.”

Under that umbrella, promotional products become a Swiss army knife serving a multitude of needs. They garner media coverage in an increasingly desperate scramble to draw free attention. (Grubbs notes how dozens of major media outlets and websites highlighted Paul’s offerings when the candidate’s store was launched last year.) They align with the swelling emphasis on digital engagement, empowering (and then rewarding) everyday people to vote with their pocket books.

Perhaps most importantly, they carry an overarching message that has become the essential currency of elections. Before, political merchandise would simply feature a name of the candidate and maybe a slogan. The items were essentially a fill-in-the-blank for supporters to make their own statement.

Today, presidential campaigns more completely understand the power of the imprint. They have created in-house teams to help penetrate the furthest reaches of their supporter base. Like a handout at the door of a community meeting, promotional products set the agenda by carrying the message and guiding voters along the thematic path that campaigns have carefully constructed – a trail to lead them all the way to the White House.

– Email: cmittica@asicentral.com; Twitter: @CJ_Counselor

Bringing Back Made-In-USA

In a January meeting with The New York Times Editorial Board, Donald Trump promised a 45% tax on all products imported from China as a way to grow American jobs. Trump backed off slightly from that figure in a March debate but still assured tariffs and punitive actions would be placed on China, as the Republican frontrunner continues to make domestic job growth a central part of his campaign. But will a tax work? And what needs to be done to grow U.S. manufacturing jobs?

Trump’s posturing does hint at the fragile state of American manufacturing, which lost 5 million jobs from 2000-2014. The specter of reshoring – bringing manufacturing jobs back that were shipped overseas – gained momentum a few years ago, but the actual results have been mixed. Studies show that U.S. manufacturing imports have increased beyond their pre-recession peak, and while 217,000 manufacturing jobs were added in 2014, only 27,000 were added last year.

Proponents of American manufacturing appreciate Trump’s intentions but don’t agree with the methods. “I think there is a space between giving China a blank check, which is pretty close to our existing policy, and the 45% tariff,” says Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing. Paul supports free trade but feels that the United States could exercise leverage and more tightly enforce its trade policy with China.

How can jobs be brought back? Scott sees a number of potential initiatives, including creating a more competitive dollar in foreign markets and building up a training ecosystem to replace the country’s aging manufacturing workforce.

As it applies to the promotional products industry, Michael M. Woody, president of International Marketing Advantages Inc., believes industry companies have to drive the change. There are factors in their favor. Demand for customized products with shorter lead times and a heightened emphasis on supply chain transparency will allow Made-in-USA companies to carve out a successful place. “I believe that supply chains are going to contract geographically in order to deal with the need for speed,” says Woody, who has written about the promotional products exodus from the U.S. and potential return back in a book titled American Dragon: Winning the Global Manufacturing War Using the Universal Principles of Fewer, Faster, and Finer.

Woody predicts there will be increased reshoring and near shoring in the future but warns it will be a long process. He also cautions that trying to recapture the peak of American manufacturing is far from feasible. “It’s not a question of winning everything back from China,” he says. “We don’t need to do that. We need to win just our share. If we take 10% back from China, that’s going to make a huge difference in our manufacturing base.”