June 05, 2017

Promotional Product Sales Compensation Survey

Distributors are increasingly choosing salary over commission to compensate sales reps. What’s behind the shift?

In Chris Sinclair’s first year in the promotional products industry in 2003, he logged 50 hours a week as a commissioned sales rep. His entire first year’s earnings: $10,000.

Four years later when he and another partner opened Brand Blvd (asi/145124), they paid their reps under a similar model. As the St. Catharines, ON-based distributor continued to grow, Sinclair and company adapted their approach to compensation, striving to create an investment in its people and the team. Finally earlier this year, each salesperson was earning under the same plan: salary plus commission plus bonus, broken into 60% personal goals and 40% team performance. “It’s really advanced our culture and created a team atmosphere,” says Sinclair, the company’s vice president. “Our plan invests in people because it takes time to build your business. We want to give them a base to get their feet wet. It’s hard to attract new hires to 100% commission.”

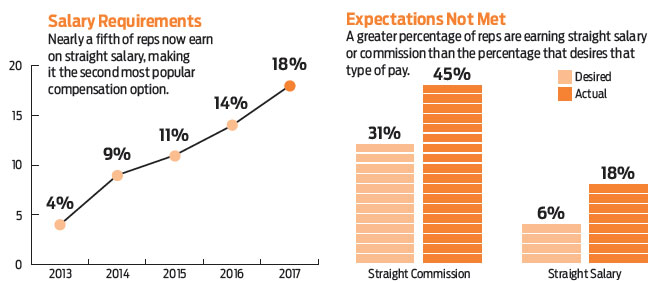

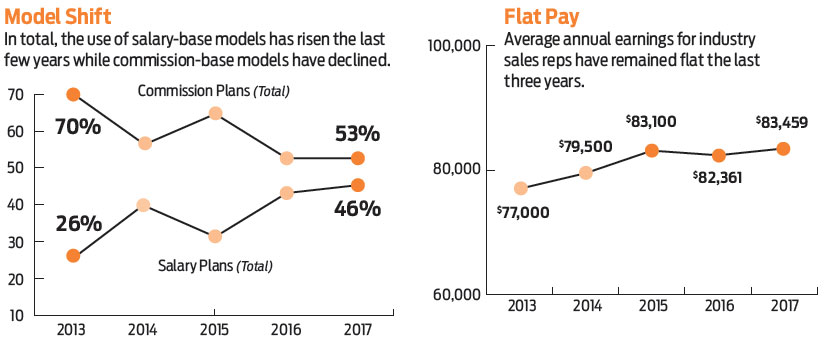

This dawning realization is driving a significant shift in how industry companies attract and compensate their sales reps. The annual Advantages Sales Compensation Survey found that more than half (53%) of all reps and managers are paid through commission-based plans, making them the primary form of compensation in the industry. Four years ago, two-thirds of reps and managers were paid in commission.

What’s replacing commission? Salary-based compensation. Four years ago, a quarter of reps and managers were paid in salary only or hybrid salary plans (salary plus commission, salary plus bonus and all three combined). Today, 46% of reps and managers have a salaried position. And the greatest driver of that growth is the prevalence of straight salary, which has reached 18% with an average increase of 3.5 percentage points each year since 2013.

Distributors point to changing employee expectations as the main reason industry companies are lessening their reliance on commission. “The younger generation is coming in and they’re just not as likely to accept commission only,” says Dale Limes, senior vice president of sales for HALO Branded Solutions (asi/356000), which has more than 800 sales reps nationwide that work on straight commission. “The sky’s the limit with commission, though there’s more risk. The younger generation’s mindset is that they have this college degree, and they want the salary that goes along with it. It’s how they’ve been conditioned over the years. Previous generations knew you reaped what you sowed, so you had to work for it.”

Jordy Gamson, president of The Icebox (asi/229395), says his company currently offers salary plus commission to their 22 sales reps. “It’s a shifting pendulum, and it’s a constant debate here,” he explains. “We want to keep a piece of their compensation tied to a variable, but it’s easier to attract people with the salary because everyone has guaranteed bills.” Gamson also says the industry shift is driven by the frequency in which workers change jobs. “They don’t look at one job as a career anymore,” he says. “They don’t plan on staying more than a few years. It’s ‘good for now.’” Because of that short-term view, sales reps in general are less willing to pay their dues and build a book of business over the span of years, which later on can reap very lucrative results through commission.

Ron Baellow, president of Bright Ideas (asi/146026), says he’s seeing the shift in the larger world of entrepreneurship, not just among millennials. Since his first job out of college, he’s followed in his father’s footsteps as a 100% commissioned sales rep; now, the straight commission model is becoming less and less desired in sales across all industries. “You have to work really hard the first couple years to build your book of business, but people aren’t willing to do that,” he says. “They see someone who’s really successful, and they want that success, but they don’t see what they had to do to get there. They’re ready to leave at 5 p.m. People just really value their free time now.”

The nine reps at Bright Ideas receive draw against commission. Baellow considers it a salary (with an amount and timeline determined by industry experience and personal requirements) that works as a training expense. “We develop a plan for them to get to their compensation goal by first providing them with a salary, and then transitioning to a draw,” he says, pointing out that a fresh college graduate has different compensation requirements than someone with 15 years of post-college industry experience who’s married with kids. “We say, ‘Tell us what you need, and we’ll put you on a plan to get there.’”

It comes down to financial security, says Jen Lyles, lead ignitor/co-owner of Firesign Inc. (asi/522741), who has her own book of business along with one other colleague. Those with families especially don’t want to take as much risk. “My sales rep would rather have a cut in commission for more guaranteed salary,” she says. “Some live for the carrot. Others say, ‘You can keep your carrot. I just want a roof over my head.’”

At Summit Group (asi/339116), sales reps are offered salaried and commissioned plan options. Director of Sales Michael Londe says, in light of the Advantages survey data, he talked to two reps (who are receiving salary plus bonus), about how their compensation model appeals to them. “There is comfort in knowing what your paycheck will be every two weeks,” he says. “The thought of the ups and downs of straight commission is scary for them.”

One account manager in the industry, who’s been in the workforce post-college for nearly a decade and at a distributor for about four years, says a plan that includes at least some salary is personally appealing and also popular with his millennial peers. His company offers a salary plus commission plan. “Everyone has solid bills each month, so it’s good to know you have that regular paycheck coming up,” says the account manager, who asked to remain anonymous. “It offers more stability. Your landlord isn’t going to wait two months for your rent.”

He points out that, in this industry in particular, clients’ invoicing terms affect when a sale is actually posted. A sale made in April, he notes, might not actually be paid until August; a commissioned sales rep then isn’t bringing in money for a few months. “Making the numbers isn’t a problem,” he says. “It’s when they actually post that can be a challenge.”

To be clear, the switch to salary isn’t just a matter of making reps feel secure. Distributors and sales organizations in other industries have switched to commission-free sales for a number of reasons, from eliminating unwanted competition among reps to shifting the focus from individual earnings to the company’s profit. Thoughtworks, a software company, switched to straight salary five years ago because customers had already researched vendors and pricing online, so the company didn’t need its reps to explain such things at the start. “Commissions,” Craig Gorsline, the company’s president, told The New York Times, “were getting in the way of a proper dialogue with our customers.”

Future Earnings

Distributors believe that a hybrid model incorporating salary and commission will be the industry standard in the near future – even if salary constitutes just a smaller portion of earnings. “Most [of my peers] have some kind of salary, whether it’s more than the commission or just enough to get by,” says the anonymous account manager. “Hybrid plans are the way it’s going.” No matter what, the implication is that commission only will cease being the predominant standard in the industry.

That can radically change how distributors operate. Londe foresees industry-wide repercussions if distributors increasingly opt for straight salary pay. “It means less incentive to go out and hunt for new business,” he says. “Companies would need a true business development team to bring in the business for someone else to take care of. With commission, the salesperson both hunts and services. But if there are fewer hunters because of straight salary, that could benefit the commission sales rep who actively searches for new business.”

Limes believes that paying straight salary can be a “slippery slope,” since it’s challenging to compensate everyone in a way that’s commensurate with performance. “Distributors will find that those who sell a lot and are way over the sales curve are underpaid, and those underselling cost the company money,” he says. That could cause top performers to go elsewhere to pursue better commissions, while underperformers will stick around with a salary security blanket.

Is the increasing prevalence of salary having a downward pull on how much reps are taking home? Compensation has stayed flat since 2015, measuring this year at $83,459. Limes thinks the lack of growth is more likely influenced by cost of living that has largely plateaued. “Compensation should adjust depending on how the rep is performing,” he explains. “But cost of living and inflation have also stayed about the same the past few years.”

The reality may be that today’s reps don’t prize maximizing their earnings. A survey by Glassdoor.com found that only 12% of respondents labeled Compensation and Benefits as the most important factor in employee satisfaction – least among six choices. (Work-life balance was next to last, while culture and values was tops.) “The culture of a company is the most important asset it can have, even above money,” says Limes.

And the culture of many workplaces now is the security of salary coupled with the flexibility that technology offers. “Gone are the days when you clocked in and clocked out at a set time, and grinding out a 70-hour week,” says the account manager who’s been in the industry for four years. “It’s much more fluid and flexible. You can make your own hours, as long as you hit your numbers.”

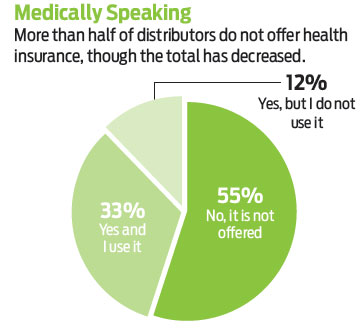

Healthy Choice

More employers offer health insurance to appeal to reps.

Distributors continue to add to their menu of company benefits to remain competitive with both new hires and current employees. Perhaps the most significant is healthcare, which is offered by 45% of distributors – the highest since 2014.

“The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has had a big impact on those numbers,” says Craig Nadel, president of Jack Nadel International (asi/279600), which has about 125 sales reps. “Certain companies, depending on size, are now required to offer it, while independent contractors can get it on the open marketplace. Changes in the law and how it’s enforced under the new administration will undoubtedly change the numbers again.”

The increase in the percentage of industry companies offering health insurance runs counter to general U.S. economic trends. Just 29% of American small businesses currently offer health insurance, a decline of 10 percentage points since the passage of the ACA (compared to a seven percentage point drop from 2001 to 2010). While average premiums for individual health insurance plans cost $2,889 per employee in 2001 (according to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey), the cost was $5,963 in 2015.

Still, smaller distributors are taking the leap to attract better reps. Bright Ideas chose to offer health insurance two years after more than 16 years without it. “We bit the bullet to be more competitive,” says President Ron Baellow. “New hires and current employees were asking about it. When the ACA was first being discussed, people were running scared because they didn’t know what the rules would be.”

Other distributors that don’t choose to offer health insurance recognize they have other means of drawing employees. For example, Firesign pays for employees’ Sam’s Club and Costco memberships. “You have to find perks you can offer that won’t break the bank,” says co-owner Jen Lyles. “People love that we do this. It’s the little things in life.”

Ours or Yours?

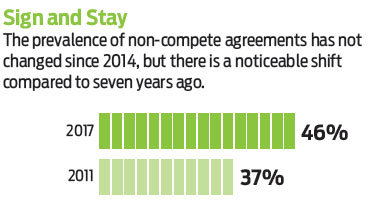

Ownership of accounts prods distributors to hand out non-competes.

The prevalence of non-compete agreements has increased slightly each year from 2011 (37%) to 2016 (47%) and dropped by a single percentage point in 2017, according to the Compensation Survey. Industry sales managers and reps attribute it to increasing consolidation within the industry and smaller distributors proactively protecting their business.

“We don’t require them, because we consider the sales rep the owner of the account,” says Dale Limes, HALO’s senior VP of sales. “But we’re seeing smaller distributors asking their reps to sign them now when they didn’t have to before. It’s hard to do that after they’ve been with them for a few years. The employee says, ‘Why? What are you afraid of?’ It’s not a pleasant situation.”

The Icebox requires everyone to sign a non-compete because of their specific business model: Leads are fed to account managers, who are matched up with the prospective clients, and every contract is put in the company’s name. “It’s different if you give them a phone and a laptop and say, ‘Go get ‘em, Tiger,’” says President Jordy Gamson. “We offer salary, training, leads and the opportunity to make money. For you to leave and go work for a competitor, we’d be wronged by that.”

Chris Sinclair says all accounts at Brand Blvd belong to the distributor, and thus has required non-compete agreements since its inception almost 10 years ago. That also allows the company to maintain control. “Sometimes there’s a certain entitlement around commissioned salespeople, that these are their accounts and they’ll dictate how things will be, how they’ll operate,” says Sinclair. “And the owners don’t want to ruffle feathers because their reps make money. But who’s actually running the show?”

The ultimate objective, says Summit Groups’ Michael Londe, is for the company to protect themselves while the reps are free to make professional choices. “The goal should be a fair deal between the company and employee so that no trade secrets or key accounts are taken,” he says, “but the employee also has the opportunity to earn a living if they go elsewhere.”

Sara Lavenduski is the senior editor for Advantages. Tweet: @SaraLav_ASI. Contact: slavenduski@asicentral.com